The following is the first Chapter for your reading pleasure.

The Squire’s GrandDaughters Chapter I

Angela Raeburn who had grown into a beautiful young woman, did not realize that her adoptive mother Mrs Bleakly was hiding Angela’s true identity of high social status and wealth from her, and that certain people known to her were plotting to gain her romantic favor and therefore the wealth that was unknown to Angela at that time.

Angela and Mrs Bleakly lived in Denehollow where the good folks kept early hours. “Early to bed and early to rise” was regarded by them not only as a time worn maxim but almost as a religious observance.

The primitive little village would have been in misty darkness by ten o’clock every night, save for the few lights that illumined the straggling streets and the red glow of Dr Pilrig’s lamp, a professional beacon which was well-known for miles round Denehollow, Dr Pilrig being an old inhabitant and skillful practitioner.

The clock on the chimney-piece in Mrs Bleakly’s parlour had just chimed half-past nine and her visitor, an attenuated, sanctimonious looking man, rose to take his leave.

“I am afraid I have outstayed the bounds of an ordinary call, my dear, madam,” he said, grasping the widow’s hand with pastoral tenderness. “Besides, I fear I am keeping Miss Angela from the pleasure of your society by remaining longer. She generally absents herself on the occasion of my visits, I notice with regret.” and the speaker sighed and cast his eyes upwards towards the ceiling with a resigned expression.

Mrs Bleakly echoed his sigh and shook her head mournfully. “I am sorry to say that Angela is sometimes rather flippant. A grave, improving discourse is wearisome to her. She has admitted as much.”

“Well, well, we must not be hard on her, my dear madam, she is very young, and no doubt sobering influences will tell upon her with advancing years. We must not forget that we were young ourselves once, Mrs Bleakly, eh?”

“It is very good of you to make excuses for her, Mr Sturgis, but really Angela’s indifference to the good work we both have at heart is very disappointing, … very distressing, I may say. Still the child has her good points, I will not gainsay that. She is affectionate, industrious, unselfish, and, … hush, here she is! Do not let her think we have been talking about her,” said Mrs Bleakly hurriedly, as a tall, graceful girl entered the room, followed by a huge deerhound. Who catching sight of his pet aversion, Mr Simon Sturgis, the hound uttered a low growl, and in passing him momentarily displayed a very formidable set of teeth.

“Angela,” exclaimed Mrs Bleakly angrily, “how often have I told you not to bring Grim into the room when Mr Sturgis is here? Turn the brute out at once.”

“Certainly. I was under the impression that Mr Sturgis had gone,” said Angela, acknowledging that worthy with a polite though rather distant bow. “Come Grim.”

The dog raised its large eloquent eyes to her face, and at a signal from her, trotted submissively from the room. Mr Simon Sturgis breathed more freely, and possessing himself of his hat, began to draw on the left hand of his black kid gloves.

Angela Raeburn was a beautiful brunette. The delicacy of her ivory skin was enhanced by the luxuriance of her hair, while her eyes were dark and fathomless and shaded by long curved lashes, that threw shade upon her cheeks. She was carelessly attired. Her severely plain white dress was confined at the waist by a leathern belt and had the appearance of being somewhat outgrown. She looked about twenty, but was in reality nearly three years younger.

Angela had been accustomed from her childhood to call Mrs Bleakly “Aunt Dorcas” but they were in no way related, and as the years passed, and Angela grew from a child into a distinguished looking girl, their incongruity became more apparent.

Mrs Bleakly had never possessed any beauty to boast of, and now that she was verging upon fifty her faded face presented a strange contrast to Angela’s youthful grace and sweetness. Mrs Bleakly was quite as dreary as she looked, and was disposed to mistake bitterness and austerity for religion, a mistake, by the way, which is often made by well-intentioned people.

Mr Simon Sturgis was ostensibly a fervent philanthropist, and a shining light at Little Bethel, where he and his near neighbour and friend, Mrs Bleakly, were regular attendants. He was superintendent of the “Young Men’s Social Club,” and honorary secretary to “The Denehollow Temperance League.” In brief, he was a sort of deputy shepherd to his pastor’s, Mr Elgood, flock. Despite all his excellent qualities he was not a favorite in the village, his appearance was distinctly unpleasing, and his manner at once cringing and hypocritical.

His eyes followed Angela furtively as she moved about the room.

“Will our dear young friend accompany you on Friday, Mrs Bleakly?” he asked, apologetically behind his hand. “It will be, I venture to hope, a well-attended meeting and our worthy and zealous neighbour, Mr Sowerby will doubtless improve the occasion, in the absence of Mr Elgood.”

“Then I am sure I will stay away,” said Angela decisively, “for I don’t like Mr Sowerby!” And she cast a mutinous glance at Simon Sturgis as she spoke.

“Not like Mr Sowerby, Angela?” repeated Mrs Bleakly in indignant protest. “Of what can you be thinking? Mr Sowerby is a most excellent man, whose addresses are extremely improving. It is a privilege to hear him!”

“A privilege of which I am not desirous of availing myself,” said the girl, with a mischievous little laugh. “Mr Sowerby is a brute to his family, and a selfish, uncharitable man, for all his professions!”

Simon Sturgis and the widow exchanged glances of consternation. What was to be done to reduce this outspoken young person to a proper and fitting state of submission?

“Our sweet young friend has the courage of her opinions,” said the former, and a close observer would have detected a smile on his thin lips. “Well, I must be going, my dear madam. Good evening, Miss Angela. I trust you will think better of your determination not to be present at our gathering on Friday.”

With that, Mr Sturgis shambled out into the passage where he was followed by the widow, who accompanied him to the front gate.

“I want to consult you about Angela, Mr Sturgis. I intended doing so tonight, but she came in inopportunely. You remember the conversation we had about her some years ago, when you undertook to keep the letters and other small articles relative to her parentage safely, until she or I required them?”

Mrs Bleakly wondered why Simon Sturgis turned so pale and feared for the moment that he might have lost or mislaid the documents, but his next words reassured her.

“The matter is quite safe in my hands,” he said hurriedly, looking past her into the lighted passage where Angela was flitting to and fro, making some preparations for the evening meal. “I will call and discuss the matter with you at greater length in a few days, but I strongly advise”, here Mr Sturgis became extremely impressive, and laid his hand momentarily upon Mrs Bleakly’s arm, “I must strongly advise that our dear young friend should be kept in ignorance of her probable wealthy connections, otherwise she may become unsettled by the prospect of the uneventful life that lies before her.”

“Certainly, of course, though I daresay she would not thank me for so doing,” said Mrs Bleakly, with a plaintive sigh. “Young people are so ungrateful for one’s solicitude. I would rather see her dead than restore her to a position in life which would be nothing short of destruction to a girl of Angela’s temperament. Although I have brought her up so strictly, I know well enough that she chafes at the restraints of our community, but,” continued the widow unctuously, “I love her too well to allow her discontent to weigh much with me.”

Simon Sturgis breathed more freely. He had begun to fear that Mrs Bleakly had some ulterior motive. “You are right, my dear friend. A life of frivolity amongst cosmopolitan people would have the most harmful effect upon your adopted daughter. Hard living and humble surroundings may not be to our sweet young friend’s taste, but it is a wholesome discipline for her future well being. You have no intention of seeking to restore her to her father’s family, I trust?”

“None whatever,” said the widow emphatically. “It is because I am afraid they should trace her and call upon me to give her up after all these years, that I wished to consult you. You have her true interests at heart, I know, and will help me to guard her from any possible contact with her relatives. I cannot part with her,” said the widow with unusual fervour. “I love her dearly, much as I should have loved my own daughter if she had lived. She must stay and be a prop and staff to my declining years. I do not think that is too much to ask when I have loved and cherished her for nearly seventeen years!”

Simon Sturgis pressed her hand sympathetically, and watched her re-enter the cottage, before heading on his homeward way.

The house he occupied was at the farther end of the village street, a dull, isolated habitation, surrounded by dank, moss-grown brick walls, and shut in by massive iron gates, eight or nine feet high. The garden was small and shady, the paths green with moss and the lawn of that rank growth which suggests a churchyard. Altogether it was a dismal abode, but it suited Simon Sturgis, who was of a melancholy and inhospitable turn of mind, which predisposed him to a life of austerity.

In this cheerful habitation he lived quite alone. He was unmarried and even the old country woman he employed to clean the house at stated intervals, knew little or nothing of his home life, for she

was always expected to leave by five o’clock, and during the time she was at work Simon Sturgis kept a vigilant eye upon her movements, lest she should be impelled by curiosity to make a closer inspection of his bachelor quarters than he deemed desirable. Any chance callers he had, he generally interviewed at the gate, no matter what the weather chanced to be. While he never invited people into the house, they felt that his lack of hospitality was due to the fact that the rooms were bare and unfurnished. Mind you, there were others that thought he had something to conceal besides shabbiness. The majority of the Denehollow folk were inclined to take the latter view, and looked askance at a man who so lacked any gregarious instinct.

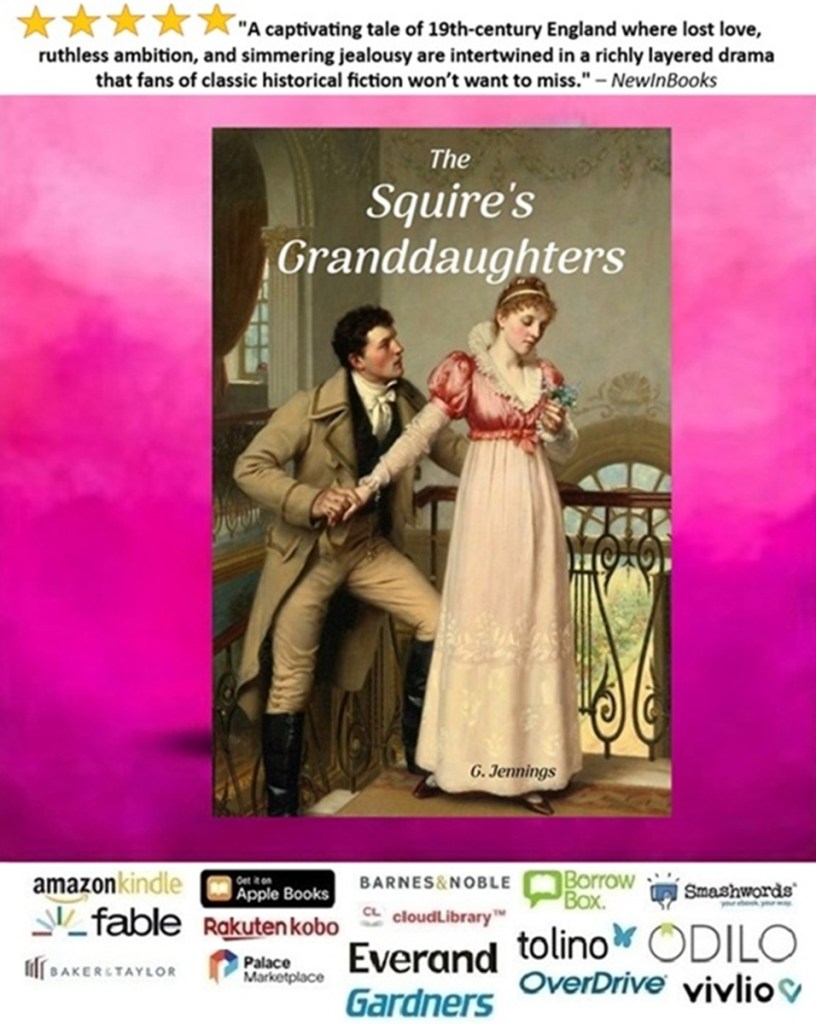

**** Obtain the remainder of this enjoyable Book or eBook at many online stores including Amazon, Apple and Fable. Some links are shown below

https://www.amazon.com/dp/B0FF3RBZ9Z

https://books.apple.com/us/book/the-squires-granddaughters/id6695758298

https://fable.co/book/x-9798227753946